The history of thrifting : the Victorian way to fight fast fashion!

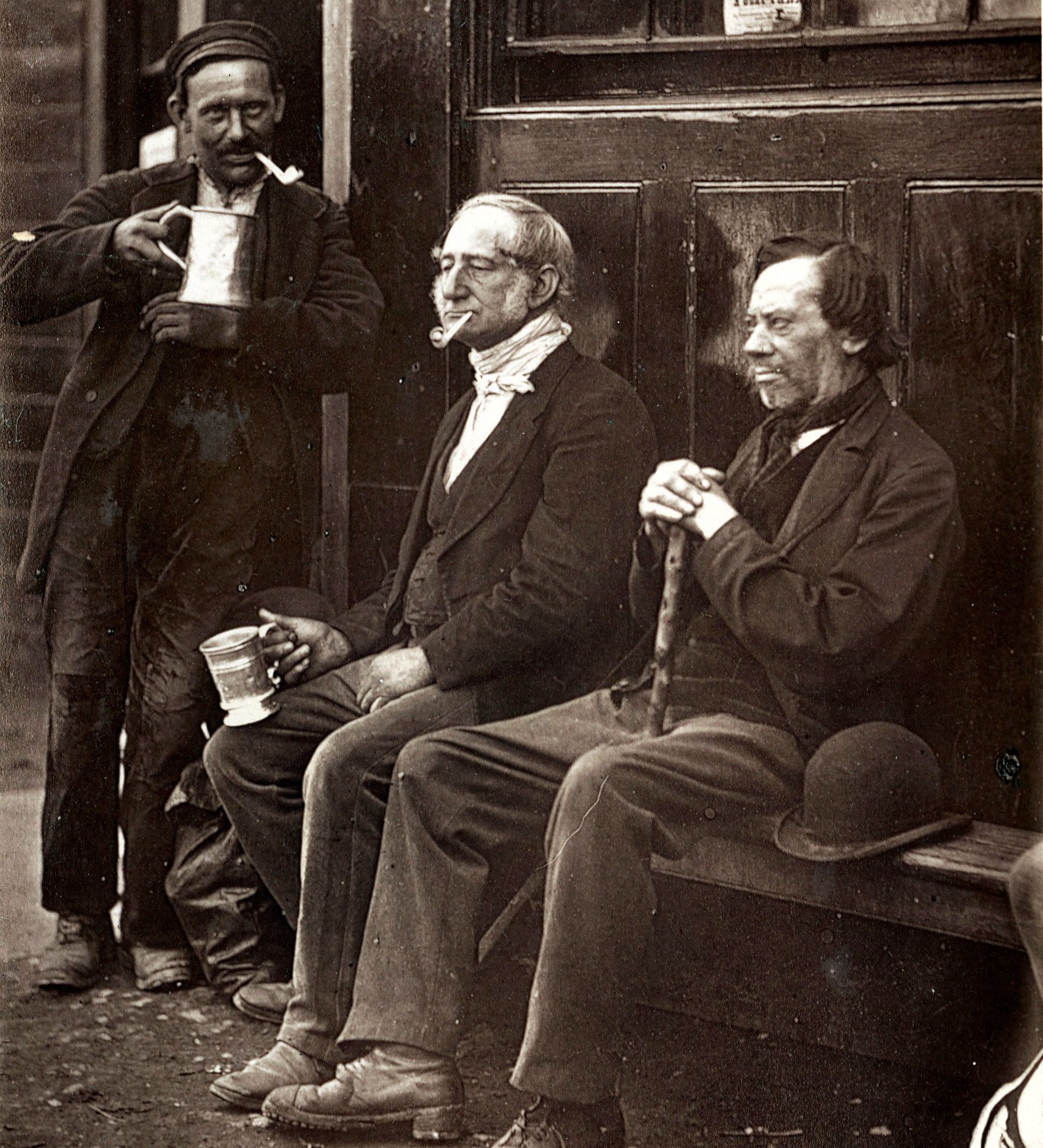

A Victorian thrift store, from "Street Life in London", 1877.

The history of thrifting : the Victorian way to fight fast fashion!

The Victorians loved thrift shopping, and it goes back a lot further than the Victorians! Time for a deep dive into the history of the secondhand clothes trade and its role in fashion history. As usual, a lot of the problems of the modern fashion industry (like low-quality fast fashion) are not as old as we think . . .

Thrift shops have existed at least since the 17th century, if not before; there was a guild for secondhand clothes dealers in Venice at that time. By the 18th century thrifting clothes was common in urban areas. They were often brought into the secondhand market by domestic servants, who would traditionally receive gifts of cast-off clothes. It’s possible that some were also brought with enslaved people as they self-liberated, to take back some of the value of the labor and freedom that had been stolen by their captors. The used clothes trade took many forms, from successful and well-established “clothes brokers” who ran full-time thrift stores, to tailors who accepted unwanted clothes as a credit towards making new ones, street sellers, and more. One woman in 1770 was running a moderately prosperous thrift store out of the front room of her house!

Used clothes were less available outside of cities until the 19th century, because the second hand clothes business couldn't get well established there without trains. Once this was possible, the social changes of the 19th century caused the trade to expand. Working-class men living in cities would buy their clothes secondhand, since they could get better quality tailored garments for a fraction of the price of newly-made clothes. While womenswear wasn’t traded quite as often, secondhand silk dresses were considered a huge bargain, and washable cotton dresses for everyday wear were so ubiquitous they were popular as well.

“Fashions used to last a lifetime, and coats were worn till their owners tired of them, and they went down the scale respectable to dress the laboring classes. But laborers now ape their masters and buy at first-hand . . . ”

A Victorian secondhand-clothes dealer’s complaints about the decline of the used clothes business could easily describe the fast fashion industry today. The industrial revolution changed the history of thrift shopping, causing well-made and long-lasting secondhand clothes to be replaced by newly made garments of "shoddy" manufacture and inferior quality. Buying newly-made items of all kinds became such a mark of even moderate status and wealth that high-quality secondhand clothes were no longer as popular as new ones, no matter how much better-made the thrifted clothes were. This is why it's so important we remember the role thrift stores played in fashion history. We can learn to be more eco-friendly and dress better by taking a few lessons from Victorian thrifting!

-

When I was putting together a costume for my first historical reenactment event, I had waaaay too much fun reading the performer costume guides. I’m a history nerd, it’s what I do. Aaand in a very-in character moment, I read one little throwaway line about how there was a thriving secondhand clothes trade in Victorian London and I got CURIOUS. You’re telling me Victorian era thrift stores were a thing?

Hi, I’m V: Fashion history nerd and extremely prone to falling down research rabbit holes thanks to random sentences on historical blogs. I absolutely love modern-day thrift shopping, and as it turns out, people two and three hundred years ago loved it just as much.

Here’s our obligatory little scope disclaimer : This video focuses on the history of used clothes roughly between the years 1700 and 1900, in Western Europe and colonized North America. It looks like the most detailed English-language records and research are from London, since the English trade was centered there. My favorite thing in the comments of my videos is when people share stories from places I don’t know about; the comments section on my Medieval Laundry video was downright fascinating. If you know about historical thrift shopping in other places, get down there and share! I can’t wait to read them.

People used to buy secondhand clothes for most of the same reasons we do : It’s less expensive, it’s less wasteful, and you can get nicer things for the money you have. I’ve always preferred getting my clothes secondhand, including some of my favorite historical or historybounding pieces. This white blouse you’ve seen in several previous videos was bought as part of my Dickens Fair costume in 2019 from thredUP, an online thrift and consignment store, so I am extremely pleased to introduce them as the sponsor of this video! I’m pretty particular about my clothes, and thredUP makes it easier to actually get what I’m looking for than going around to all my local thrift stores hoping I’ll find something specific. Especially nice when all those stores are closed or don’t have fitting rooms thanks to a global pandemic, buy they’ve been my go-to clothing store since I heard about them several years ago. I haven’t really shopped for clothes much during the past two years both because it wasn’t as safe to shop in-person, and because there didn’t seem to be much point to wearing anything interesting? Changing out of my pajamas makes me feel much more energized, though, so I’m finally updating my closet with some everyday pieces that will be easy to wear, work with the historical garments I’ve made, and add a little more historybounding flair. It’s still sweater weather in the Bay Area, and this Rachel Parcell one looks a lot like 1890s sport sweaters! It’ll go perfectly with a black wool walking skirt I made, custom-order 1890s reproduction boots, antique black leather gloves, and my black felt hat. Oh, and a trusty hatpin, in case of unpleasant winds or unwanted company.Once it does finally warm up, this Zara TRF blouse will be perfect for Edwardian spring outfits! The insertion lace and embroidery are just wonderful. I’m wearing it with a linen walking skirt, antique lace gloves, and a giant straw hat with even more hatpins. These striped linen pants from Anthology also reminded me a lot of Edwardian sportswear, and they were only $29.99 instead of $149 estimated retail. They’ll go beautifully with another fluffy white Zara TRF blouse, and of course the gloves and hat. If I can’t be bothered to put together an outfit, a cute dress with some historical inspiration will spare me the trouble. This Moulinette Souers dress, another amazing deal at $35.99 instead of $167 bucks, has major 1950s vibes, and the only accessory I need is bright red lipstick. (although, stockings and vintage-style heels are also an option). And for when I actually just need to stay in my pajamas, I can still feel good about my outfit with a pair of Sohalia lightweight cotton wide-leg pants, and one of my hand-sewn rectangular-cut linen tops. For when my toes inevitably get cold, I got these Stars Above slippers, which were an amazing price for being real leather! If you also could use some sustainably-sourced historybounding pieces to make getting dressed in real clothes more fun, you can get 30% off your first order from thredUP and free shipping with code SNAPPYDRAGON using my link down in the description.

These days, fast fashion has made it possible to clothe oneself in newly-made garments for a relatively small financial cost, albeit at a much greater environmental one. We’re not going to shame anyone who relies on fast fashion’s low prices to stay within their budget. The industry’s destructive environmental practices are solidly the fault of large companies, not of individual people doing the best they can. A few hundred years ago, though, clothing was extremely expensive, even the most basic everyday things. It takes a lot of work to process raw materials like wool and linen and cotton into fabric, and before industrialized textile production, even cheap fabric cost a lot more compared to the other costs of living. No one with any sense would throw away a piece of clothing, even if they didn’t want it. This led to almost a sort of zero-waste philosophy that works out similarly to our modern-day reasons for thrift shopping. With the amount of resources that went into manufacturing textiles, financial and ecological waste were not really separate things.

A lot of the clothes in present-day thrift stores come from regular people getting bored of their clothes and cleaning out their closets. In the past, much of the secondhand clothes trade began with domestic servants, whom there were a lot of. It was once said to me that in 19th century society “either you had servants, or you were servants”. That’s probably oversimplifying, but given that domestic service was the second-most common occupation in the 1851 UK census, and the most common 20 years later, it’s at least a reasonable one. As far back as the middle ages, it was traditional to give clothing to one’s servants, either as part of their wages, as a uniform, as charity, or simply as part of the social code that governed domestic service. Upon an employer’s death, a 19th century ladies’ maid “might expect to inherit [her employer’s] whole wardrobe, with the exception of items of lace, fur, velvet, or satin”. Maybe this was a sort of severance pay, since the maid would need a new job? However, many of these cast-off or gifted clothes were not appropriate for a full-time servant to wear. Either they couldn’t wear them while doing their jobs— you do not want to be working around an open fire with big ruffles on your sleeves— or it was considered socially unsuitable for a working-class person to dress in very expensive clothes. If you were given a costly silk dress that you couldn’t wear, the only thing that made sense to do was to sell it and put the money towards something you could actually use.

In addition to cast-offs and traditional gifts, some of these clothes may have been taken under much harsher circumstances. Rebecca Fifield has made an amazing study of the clothes described in ads for indentured servants and enslaved people who escaped their captors. Often times it’s to help identify the person described, hence the paper’s title “Had On When She Went Away”, but many ads mention people taking away extra clothes in addition to what they wore. Sometimes these were things they might use themselves : A Black woman named Beck “stole a black crape gown” when she liberated herself. “Crape” was a fine material, often a wool and silk blend used in fancier mourning dress. However, sometimes these were items that the person would be unlikely to wear. The same ad tells us that Ann Wainrite, an indentured servant who Beck went away with, “hath taken with her a striped cotton shirt, and some white ones, a drab-c[o]lour’d greatcoat, a silver-hilted sword . . . with a considerable parcel of other goods”. ‘Shirts’ were menswear garments at this time, the womenswear equivalent being a shift or smock. Clothes might have been an ideal item to take away when someone was self-liberating. They would fetch a decent amount if sold, were universally owned and traded, and would draw less attention in the hands of a working-class person than, say, jewelry. A classy gown like the one Beck took away with her might help finance her escape and emancipated life, quite rightly at the expense of the enslavers who held her captive and profited from stealing her labor and liberty.

Once clothes left their original owners, there were all sorts of ways they might be sold to new ones. Around the beginning of the 18th century, the “formal” English trade in used clothes was carried out by full-time professional “clothes brokers”. One shopping district was on the East side of London in neighborhoods that were less regulated, and a higher-end district was also beginning to develop in the West near Seven Dials and Covent Garden. “A General Description of All Trades”, a book describing the various trades and professions carried out in London in 1747, differentiates “salesmen” from “clothes-brokers” by saying the former deal in new ready-made clothes and the latter in secondhand. “The London Tradesman”, published by R. Campbell also in 1747 describes the salesmen’s work, saying “They trade very largely and some of them are worth some Thousands. They are mostly Taylors or at least must have a perfect skill in that Craft”. An ad for a clothes-broker in an Oxford paper from 1773 reads : “John Matthews, Salesman from London, buys Ladies and Gentlemens cast-off Cloaths, laced, embroidered, or brocaded, full-trimed or half-trimmed . . .”. He then explains that he trades abroad as well as in England, that he plans to stay two weeks in Oxford before leaving, and will travel up to 10 miles to make purchases. In addition to formal clothes brokers, there were a variety of less formalized markets for secondhand clothes. We have a record of Susannah Somers, who in 1770 ran a thrift shop out of the front room of her house. She was a small enough and informal enough businessperson that her shop is not listed in any sort of directories. The information we have about her is because her belongings were inventoried and appraised when she died. Used clothes might also be a sideline attached to a tailor or dressmaker’s business. In the January 28th 1765 issue of the Public Advertiser, a tailor named William Littlemore offers for prospective clients “not knowing how to dispose of those Cloaths they never intend to wear no more”, he will take the unwanted garments as part of a payment towards making new ones. Pawnbrokers, of which there were many, would often accept items of clothing as pledges against loans. If they weren’t redeemed, these items would also be sold on the secondhand market.

In the 19th century, London’s used clothes trade expanded greatly, largely thanks to Jewish traders. Numerous Jewish immigrants came to England from Eastern Europe and German areas. Jews had structural barriers to conventional employment, so many went into business for themselves. If they had a background in tailoring, dressmaking, or shoemaking, the largely unregulated and informal secondhand clothes trade would be a very good fit. The Old Clothes Exchange was opened by a Mr. L. Isaac in 1843 , in the Jewish quarter, and nearby the separate Simmons and Levy exchange dealt with wholesale lots of used clothes which were exported to Ireland. The export to Ireland alone was worth 80,000 pounds a year, which had the purchasing power of 8 to 10 million pounds in 2020. Greater and greater numbers of Irish immigrants also took part in London’s secondhand clothes trade. There’s an account saying that the Irish traders assimilated so well into the industry’s Jewish norms, they were indistingushable from Jewish traders. As an Ashkenazi Jew who is constantly mistaken for being of Irish descent, I find this probably more amusing than I should . . .

Outside of the exchange, old clothes had long since been traded in the streets, but this was such an informal market we have relatively few records of it. Barter was used as well as cash, including exchanging clothes for ceramics, and also for plants?! In Madeleine Ginsburg’s amazing paper on the secondhand clothes trade , she recalls a family story of a top hat in 1905 Liverpool being worth one apidistra. And finally, there were the most direct ancestors of our modern-day thrift stores : Secondhand clothes shops, most common in “artisan” neighborhoods. They were considered good businesses; a literary example has Samuel Butler’s character Ernest Pontifex earning 500 pounds a year from a secondhand shop which he opened as an ex-convict. This is perhaps somewhat exaggerated, but not so much that a reader would find it unbelievable. The improvements in railways and in the postal service also meant that secondhand shops outside of London got more of a foothold. Middle- or upper-class people who wanted to avoid the social hit of selling their possessions could write anonymously to one of the many “womens” magazines. Some of them were recommended to dealers nearly two hundred miles away.

Okay, but, what about the people actually wearing secondhand clothes? People had similar motivations for buying used clothes, or not wanting to shop secondhand, as we do today. Folks on extremely tight budgets would buy secondhand rather than going without; if a used coat was the only coat you could afford, that’s what you would get. Working and middle-class people saw an opportunity to have nicer things than they could afford if they bought new. But, there were also the same concerns about taking a hit to one’s social status by admitting you couldn’t afford newly-made things, and they grew stronger over the course of the 19th century. This is a major reason why the purchase of secondhand clothes was rarer among middle- and upper-class people. Ginsburg points out that Meg March from Little Women is upset at receiving cast-off clothes from her wealthier aunt. Getting a good fit from a secondhand item is another issue that transcends time, although it plays out very differently now given the rise of standardized sizes. Honestly, I think standardized sizes make thrift shopping more difficult than it might have been a couple hundred years ago. They’re inherently kind of a train wreck— Emily Snee has done an amazing video on why that is. In the 17th through 19th centuries most clothes were made-to-order for a given wearer’s measurements. Your chances of finding a perfect fit were maybe a bit lower, but most people either knew or lived with someone who knew how to re-fit clothes. It was a basic life skill. And, unlike today, clothes were often made with the intention of being easy to alter. A lot of 18th century womenswear is fitted primarily through pleating the fabric, either through these shaped back pleats in gowns and jackets or the waist pleats in gown skirts and petticoats. You could just undo the pleats, reshape them to your own body since all the fabric was still there, and sew them back up. If you were willing to spend a few evenings doing the alterations, you could save up to 15 shillings and sixpence off a frock coat in the 19th century.

In the 18th century, those buying secondhand clothes were either believed to be either social climbers, party people, and/or part of the underworld. This certainly did happen; we have the literary example of Fanny Hill being given a secondhand gown of white lutestring for her first, uhh, professional engagement. Of course, much of the secondhand market was made up of the large numbers of ordinary poor and working-class people whose lives weren’t considered important enough to record detailed information about. The high availability of good-quality secondhand clothes in London actually led to confusion among visitors! People were were used to being able to discern someone’s social status at a glance, and such a strong trade in used clothes improved the standard of dress to the point where that was harder. There’s a lot of commentary from the early 18th century showing that even Londoners and English people found the breakdown of this system confusing, and particularly satirizing the idea of maids dressing nearly as well as their employers. Daniel Defoe’s 1725 pamphlet “Everybody’s Business is Nobody’s Business” uses the class-transcending wear of hoop petticoats as proof that society must be unraveling (or something), saying a female domestic servant “must have a hoop too, as well as her mistress; and her poor scanty linsey-woolsey petticoat is changed into a good silk one . . . In short, plain country Joan is now turned into a fine London madam”. As for the rest of England, it seems like there was much less access to secondhand clothes in rural areas until the 19th century. Agricultural workers, who were generally low-paid and could benefit a lot more from the money they might save, would have to go to a sufficiently large town to find a dealer. During particularly hard years, some families would buy no clothes at all, either patching and mending what they had, or making do with gifted secondhand items.

The upper classes were, of course, also very concerned with displaying their status through dress. Obviously wearing fancier clothes meant you had more money and power, but that didn’t mean you could cheat the system by thrifting. Buying secondhand was considered a social faux-pas, and a double one at that. It wasn’t just that buying secondhand was admitting that you needed to mind your budget. If someone couldn’t afford to have an expensive gown made new, it was considered inappropriate to “pretend” their circumstances were better by wearing an equivalent gown bought secondhand. Instead, dresses could be remade over and over. One record describes a puce satin gown being remade at least six times over the course of a decade, before finally being “at its last gasp” in 1792.

The sale of secondhand clothes expanded dramatically in the first half of the 19th century, leading to the establishment of the aforementioned Old Clothes Exchange and other more formal avenues of purchase. The changing social order also expanded the demographics of people who either could or would buy clothes secondhand. Mail-order systems and distribution, like the ones from the English Womens’ Domestic Magazine, made secondhand clothes far more available to people in rural areas than they had been in the 18th century. Henry Mayhew describes the Old Clothes Exchange and the secondhand clothes trade in his 1851 book, “London Labour and the London Poor”. Of wider distribution networks, he says ”Tradesmen of the same class come also from the large towns of England and Scotland to buy for their customers some of the left-off clothes of London. And, the expanding semi-urban working- and lower-middle class was also in kind of a demographic sweet spot as far as the social context of buying secondhand clothes. They had strong reasons to care about their appearance, but were not afraid of showing thriftiness. This demographic change played out really interestingly in what sorts of clothes were popular on the secondhand market. Menswear was actually more traded-in than womenswear. While sewing was considered enough of a basic life skill that everyone of any gender would know how to do a little, highly tailored menswear items were usually not made at home, and men were usually not taught to make entire garments. This was the case even when there was a female member of the household who had been taught enough sewing to make basic dresses, on account of her gender. Middle-and working-class women could economize by making their own clothes from scratch, but not these types of tailored things. So the men of the urban proletariat— clerks, artisans, and so on— created a high demand for items like frock coats for Sunday best, greatcoats, and sometimes waistcoats and trousers. It was these garments that became the staples of the used clothing trade. In the same section of his book Mayhew details the process of restoring frock coats and similar garments, including re-dyeing areas near the seams that looked lighter because the fabric was worn. Trousers could be “turned”, meaning disassembled and put back together with the fabric reversed to get more life out of them. Waistcoats might have the worn edges cut away and be reassembled a size smaller. Shirts, which were easier to make at home, did not sell well.

As far as the trade in womenswear, Ginsburg says that if you want to know what items were popular, look at what’s underrepresented in museum collections. We have most of the extant garments we have because they weren’t being worn out. Working-class women were usually wearing and mending their everyday clothes until they couldn’t be mended, then cutting them down to make other items out of the fabric. “Wash dresses”, patterned or solid cotton dresses in simple cuts which were, well, washable, were the staple of everyday casual dress, and would have been popular because they were so ubiquitous. Silk dresses were also popular, not because absolutely everyone wore them, but because everyone did want them enough to consider a secondhand one a very good bargain. Kind of like how we’d see getting a designer dress at half-off as a really good deal, even if it was a little pricier than most of our other clothes. Mayhew notes that unlike menswear garments, which were usually fixed-up by the used clothes dealers, womenswear was more often sold “as-is” because the purchasers would rather make the alterations themselves, and had the skills to do so. Undergarments like chemises and drawers were popular for many of the same reasons wash dresses were : Everyone wore them, and they were also relatively unfitted so you didn’t need a perfect size match. For that same reason, corsets were not generally traded secondhand. They were much harder to clean, had to fit the wearer perfectly in order to avoid discomfort, and took much more work to alter. Cotton caps were commonly traded in the 18th century when muslin had to be imported and might not be affordable new. However, they were hardly ever bought new by the mid-19th century, because cheaper muslin was being produced in Britain and newly-made caps were no longer a luxury item.

This is pretty much how the secondhand clothes trade started to die among all but the lowest social classes. The industrial revolution’s new mechanized production methods, and said destructive colonization on the part of Western Europe, made every aspect of creating new clothes less expensive. Factories were mass-producing cheap fabric, and the general availability of sewing machines made constructing things easier too. Unfortunately, one of the major tradeoffs was the quality of these new mass-produced garments. The minimum standard basically dropped off a cliff. In 1877, in what was essentially the Victorian English equivalent of “People of New York”, John Thompson and Adolphe Smith photographed and interviewed this anonymous old-clothes dealer who complained of the decline in quality. “The country is going downhill,” he said. “Such articles were all honest wool when I took to collecting, but now flash and flimsy is the style. Steam-dressed goods, cotton and dye and shoddy’s all the rage . . . Fashions used to last a lifetime, and coats were worn till their owners tired of them, and they went down the scale respectable to dress the laboring classes. But laborers now ape their masters and buy at first-hand . . . There’s the ready made shopman— trousers ten shillings, and all the rest of it. His clothes would not be worth a bid after a fortnight’s wear . . . “. This man’s remarks could just as easily describe the modern-day mentality of fast fashion. Our social structures have come to value the novelty and perceived status of newly-made items over nearly everything else. Clothes aren’t made to last a lifetime now, because that sort of quality and longevity isn’t something most people even know how to look for. So the construction and quality and ethical standards of the clothing industry fall further and further, and the poor worksmanship of fast fashion items means they fall apart too quickly to have second lives. They become waste and pollution rather than being freshened up and made useful. All because for the past century, societally speaking, we would rather have something new than something good.

So let’s take a few lessons from our historical thrift-shopping predecessors. Let’s look at our clothes as things of value. Let’s learn to care for them properly and make them last, and learn to mend and alter them when we need to. Let’s learn to recognize good quality, good construction and ethical production standards, and prioritize them as much as we can. Those of us with the leverage to do so can try to push the industry towards better practices with our purchasing choices. And seriously, let’s lose the social stigma behind buying used clothes. If was good enough for the Victorians, the people we imagine as the epitome of stuffy and proper, it’s good enough for me. Thank you to thredUP for sponsoring this video, and for offering my viewers 30% off your first order with code SNAPPYDRAGON, using the link in the description. Tell me down in the comments about your favorite thrifted clothing find, and don’t forget to click the like and subscribe buttons while you’re there. I’ll see you again soon with more fashion history nerdiness and nonsense. Bye~