Comparing Victorian fashion magazines to Cosmo

Comparing Victorian fashion magazines to Cosmo

Fashion magazines like Cosmopolitan and Harper's Bazaar aren't new, they've existed since Victorian times! But what do they tell us about fashion history, and about what life was like over a hundred years ago? I compared two modern "womens" magazines to two Victorian ones : Godey's Ladies' Book from 1857, and Harper's Bazar from 1897, to see how different fashion magazines and the parts of life they talked about are— or aren't.

Fashion history in print

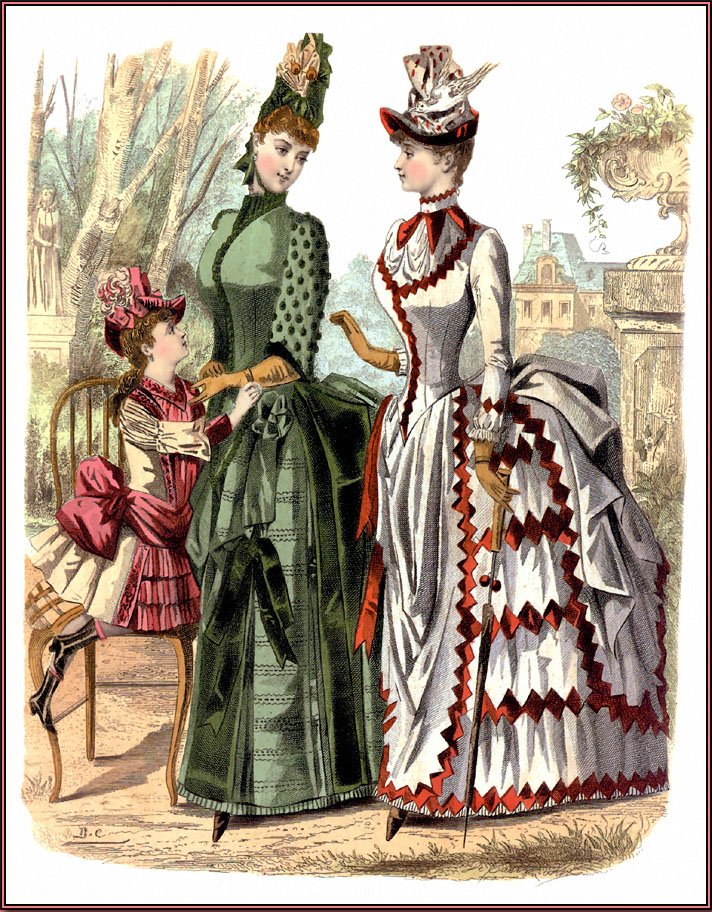

"Fashion plates" are the most common part of historical magazines for historical costumers to use, because they show us detailed pictures of Victorian dress designs. Just like modern magazines show us pictures of fashion trends, these 19th century fashion plates were to inspire the reader. The key differences in Victorian fashion plates versus modern fashion editorial photos tells us so much about the changes in how clothes are produced : Instead of combining designs we like into a customized, custom-fitted outfit, we have to choose from mass-produced options. Furthermore, they show us the huge strides we've made in representation in fashion, and the ways in which the fashion world is still lacking in diversity.

More than just fashion

But what else is in these magazines, past and present? Magazines contain a wealth of cultural information, from news and current events to literary content, reviews, and articles about pop culture. You wouldn't expect a 19th century magazine to be relatable, but they are! The Victorians talked about politics, about books and media, about cooking, about celebrity wedding . . . all things we expect to read about in a magazine today.

-

These drawings, called "fashion plates", are one of the first things you see if you start looking for pictures of historical clothes. Victorian fashion magazines were *full* of them, but there was a lot more to them then pretty pictures of fluffy dresses. It's in the Victorian era that the idea of the "womens" magazine really takes off, and I got to wondering . . . how different were those magazines from the ones we have today?

I say "womens" magazine because it's the commonly recognized genre term, not because we believe in gender essentialism here. (We don't. It's a silly term.)

Hi, I'm V, and I spend a lot of time making really old clothes. So while I have looked at plenty of Victorian fashion plates, I've never actually *read* a historical magazine cover to cover to see what else was in there. And yeah, I could have just downloaded whatever from Project Gutenberg and read them by myself, but you all wouldn't find that very interesting now, would you? Besides, everything in history reads better with some context.

So! I have gone out and purchased two popular modern fashion magazines : Cosmopolitan, and Harper's Bazaar. I'll be comparing these to two 19th century fashion magazines : Godey's Ladies Book and . . . Harper's Bazaar. Yes, it is that old. The modern ones are in print, but the Victorian ones are in digital form thanks to HathiTrust.

And, while I'm thanking providers of online learning content, I should also say thank you to Skillshare for sponsoring this video!

Now, let's do some reading!

I mostly talk about clothes here, so that seems like a good place to start. All of these magazines have both articles and visual content about the latest clothing trends, and on the surface, it's really similar! There are articles talking about what shapes and materials and colors are in fashion this season, what celebrities are wearing, giving the reader ideas and suggestions. The fashion plates in the 19th century magazines do pretty much the same job as these "editorial photos" in the 21st century. Although, some of the modern editorial photos are much, much more unwearable than anything I've seen in 19th century fashion plates. It's understood that you're not meant to completely copy any of these outfits, present or past, although you could if you wanted to. These articles and images are here to provide you with the advice and inspiration you would need to follow the fashions of your time.

The difference, is what you would *do* with that inspiration. In the 19th century, clothes were most often custom-made rather than mass-produced. There had been a bustling trade in secondhand clothes for years, and ready-made clothes were becoming more and more available, but the fashion industry's sort of "default" expectation was that you would get your clothes made by a local dressmaker. The relationship was kind of like going to the hairdresser is today {laugh}. First you would buy your fabric, usually separately. Then you would bring it to your dressmaker, or have your dressmaker visit you, and say "I like this style of bodice, the skirt from this one here, and . . . the trim from this other one". You'd talk it over, agree on a price and a finished design, then your dressmaker would make the outfit just for you, to your exact measurements. No standardized sizes, no not being able to find something off a hanger that fit you. You might also bring your dressmaker a skirt from five years ago and say "I like the draping in this picture, can you update this for me?". If you changed sizes, which people certainly did, you or your dressmaker would just alter your clothes, taking seams in or letting them out as needed. The descriptions on these fashion plates don't usually mention the names of designers, instead they talk about the shape of a skirt, how many flounces it has, how the trim is made, with the expectation that you'll mix and match elements according to what suits you. Even this swimsuit article— and yes, this 1897 magazine has a swimsuit article! —talks about the pros and cons of different kinds of fabric. Maybe you can't afford mohair, so the article will reassure you that regular wool flannel or serge will do just as well. If you don't want a huge collar on your 19th century bathing suit, then you can just have it made without one! I especially enjoyed this little snippet about how to put hidden pockets into a decorative bow on your dress, which seems just as important in the modern era of tiny useless pockets as in the time of giant skirts with pockets big enough for just about anything.

In the 21st century articles and photos, they talk about cut and material, but you're expected to choose from what's already out there, rather than designing pieces how you want them. Most of us don't get our clothes customized, we go to a store or a website and buy them already made. So what they do mention is the designers, or where the clothes were bought, which I suppose is the modern equivalent! If you're going to put together an outfit, you kind of approach this info the same way as a 19th century person would choose fabrics and trims, saying "I like this top . . . this pair of jeans, these shoes, and this necklace from over here". You look through it for what you like, think about how you might put together a look or what you can find that's similar. We definitely don't have the expectation that we could see a dress in a magazine and say "I like it, but I'm gonna get it in navy blue striped cotton instead of the pink silk in the picture".

Also, a lot of these clothes are . . . not in most people's budgets. Especially in the modern Harper's Bazaar, these are nearly all designer pieces with very high price points. I looked up the cost of this shirt, since it looked like a simple piece, and it was $1290. Yes, it's silk, but silk is nowhere near *that* expensive. In both 19th century magazines, not only is it assumed you'll customize the dress designs and fabrics to what you can afford, they even include sewing patterns so you can save even more money by making them yourself.

Speaking of making things yourself . . . let me tell you about the sponsor of this video, Skillshare! Skillshare is an online learning community with thousands of classes on everything from modern skills like web design, to crafts straight out of a Victorian magazine like watercolor painting and embroidery. I'm usually a one-woman production team for my videos, so I was super excited to take "How to Film Solo Without the FOMO: Filmmaking Tricks for the One-Person Crew" by Dandan Liu. She talks about intentionally and purposefully building storyline to guide a video and do more with your footage . . . so, of course, my next research deep dive will be about narrative principles in filmmaking.

All of Skillshare's classes are ad-free, which is especially nice given this one took me under 15 minutes! They're constantly coming out with new classes, so I have a feeling I'm about to discover so many new skills to learn. Plus, Skillshare's classes are perfect for watching while I handsew— and I do a *lot* of handsewing. The first 1000 of my subscribers to click the link in the description will get a 1 month free trial of Skillshare so you can start exploring your creativity today! Just because modern magazines aren't encouraging us to get creative and make things for ourselves, doesn't mean we can't still learn to.

These fashion plates are focused on the clothes, but they actually tell us a lot more than what people were wearing. For those who hadn't already noticed, absolutely all of the people shown in the 19th century magazines are white. Every single one. I'm usually not a numbers person, but I counted every model, both in advertisements and editorial content in the 21st century magazines. The breakdown was 54% white and 45.6% people of Color, with Cosmo having nearly equal numbers and Harper's Bazaar slightly less. I wanted to do a detailed demographic analysis of how well the models of Color represent the actual population of the US . . . but, unfortunately, that was prevented by the fact that the modeling industry's practices actually confuse our views of ethnicity in a huge way. I was chatting with Muse of Muse and Dionysus who has extensive experience in the modeling world. They told me that it's common practice to cast models who can "pass" as a certain ethnicity or nationality even if that model is from somewhere completely different. So, an American publication might cast a South Asian model to portray a Latina, a Latina model as a Maori person, and a Maori model as a South Asian, as long as all three models have brown skin, dark hair, and brown eyes. Many of the models aren't named in the magazine, so it's not even like I could look them up to get accurate demographic information. It's ridiculous that this has to be said (and even more ridiculous that it happens), but *Brown people are not interchangeable*. Seeing any people of Color at all is an improvement on the total utter lack of representation for the 19th century people of Color *absolutely did* exist here. But . . . *wow,* that is a low bar.

There's another way these fashion illustrations aren't representing real people, and this is true of the modern ones as well : Body types. In the 21st century magazines, almost all of the models are young, tall, and slender. The modern Harper's Bazaar is notable for having one plus-sized model who did a several-page feature, but also three articles and one advertisement featuring older women. Cosmopolitan had no diversity of size or age that I could see. As for the 19th century magazines . . . Can I just point out that the people in the 19th century Harper's Bazaar plates are literally copies of eachother?! I don't mean they're similar, I mean it's literally the same drawing copied over. The faces and hairstyles are identical. So there's no diversity of age or size or race or anything else, and their "standard" human figure is of medium height, slender, and has an improbably small waist. It's a drawing, there's nothing stopping the artist from taking liberties with the proportions to sell the idea that those clothes will make you look like this fictional person. The body types shown in these fashion plates are not real people, they're representations of the unachievable *ideal* beauty standard*.* And so are the living human models in 21st-century fashion magazines! Real people don't look like these representations, whether that's because it's a drawing, or through more modern technologies like photoshop. Human beings have *never* looked like the pictures in magazines, and the pictures in magazines have never been realistic.

Another big difference between how 19th century and 21st century people would access fashion and beauty is really obvious when looking at the makeup and skincare and haircare articles in the 21st century magazines. There is very little discussion of beauty *products* in the 19th century magazines, because it was a bit of a taboo at the time to openly admit you used them, and wearing visible makeup was considered grounds for slut-shaming. In the 1897 Harper's Bazaar there are ads for face powder and moisturizer, but that's about it. What we do have from the 19th century, though not in magazines, is a wealth of recipes for making cosmetics and skincare at home. The website Kate Tattersall Adventures has a page that's just full of 19th century beauty product recipes, including rouge, lip balm, skin creams . . . So, just like buying fabric to have a dress made, or making it yourself from a sewing pattern, the average person was much more involved in producing the fashionable things they have. It's not even "DIY" because the term "DIY" implies that doing it yourself isn't normal— and in the 19th century, it was! But the 21st century articles are . . . a shopping list. It's this collection of makeup or skincare products, saying "this cream is good for this skin type", very much "go out and buy this" rather than the reader being involved in the process. It really does show this shift in attitude from creating fashion and beauty for ourselves, to . . . At best, curating a collection, and at worst, consumerism.

The 1897 Harper's Bazaar had sewing patterns for clothes, but the 1857 Godey's Ladies Book goes even further. It includes not only sewing patterns, but 16 embroidery patterns for clothing, 10 more for household items like chair covers, instructions for crafts like drawing, painting with glass, and building aquariums, and *sheet music*. The sheet music was actually a major selling point of the magazine! Remember, the 1850s were a time before recorded music, so if you wanted music you had to make it yourself. Playing an instrument was considered a good skill for anyone to have, but absolutely essential for upper- and middle-class women, as every Jane Austen novel will be happy to tell us. I figure this would be the equivalent of a magazine today coming with an album from a popular artist, which would indeed be a selling point.

These days DIY or crafting content seems to be separated into its own publications. It's great that those exist, but the fact that they are separate is just further evidence of how making things rather than buying them is the exception in life today, rather than the rule. It's a hobby or a special interest, not something with broad enough appeal to make it into a general "womens" magazine.

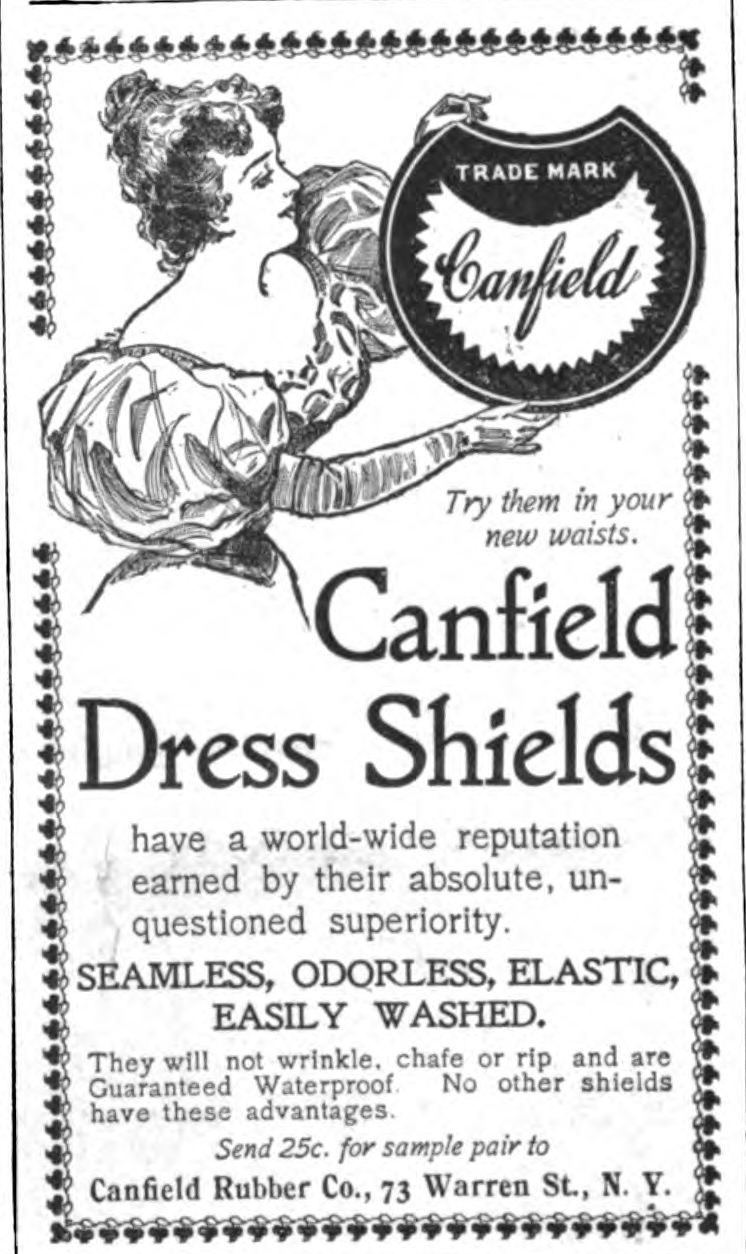

While we're on the topic of consumer culture, let's talk about the ads in these magazines. I think this is the absolute biggest difference between 19th century magazines and 21st century ones, and not even so much in what's being advertised! The 19th century ads cover everything from face cream to dress shields to baking cocoa, and the 21st century ones are a similarly broad range of everything from shampoo to medicine to pet food. A lot more of them are for beauty products in the 21st century, which is kind of a given because we can talk about the fact that we use those now. But the difference in just how present the ads are, both in size on the page and proportion to other content, is *staggering*. In Godey's Ladies' Book most of the ads are just text, in a sort of "editor's desk" section towards the back, kind of like newspaper job or personal ads. A lot of them are actually about how the magazine's fashion editor can do a sort of personal shopping service, sending away for jewelry or having dresses made for a commission from the reader. The 1897 Harper's Bazaar has ads that look a bit more similar to modern ones, with graphic design and sometimes pictures of the products being advertised. But these are small, usually several to a page. The only full-page advertisement is for another Harper's publication, the rest show up on only three pages and those pages have other content on them too. In the 21st century . . . 31.8% of Cosmopolitan's pages and 39.8% of Harper's Bazaar are taken up by ads, only four of which are smaller than one full page. Full-page ads are the norm, but double-page ones are quite common, and 2021 Harper's Bazaar has three-, four-, and even a five-page advertisement. Page 24 is the first page of that magazine that *isn't* an ad. I won't pretend that the photography and styling and all isn't lovely, but this is more than a bit much. This is without getting into the "advertorials", the beauty and fashion articles where they're recommending all the different things you could buy. I don't know enough about the magazine publishing industry to say how much of that is paid product placement— meaning, the company paid the magazine to include their product in an article— but I'm betting it's a lot more than none. The closest equivalent to those in the 19th century magazines is in some of the descriptions of the fancier fashion plates, where they mention the name of either the artist or the fashion house that designed the dress.

I don't know about you, but the idea of literally paying for something that is nearly 40% advertising feels ridiculous to me. I'm not someone who gets nostalgic to go back to the way things were in the past, because I like my modern medicine and civil rights and such, but I would be many times more likely to actually read modern magazines if there was a little more magazine and a little less trying to sell me things. Or if we can't go back to that, could we at least go back to not having those perfume ads where the perfume is *in* the magazine, and you have to smell it the whole time you're trying to do research? That'd be great, thanks.

All of these magazines except the 2021 Harper's Bazaar also had content about cooking. This is probably the topic that I am least equipped to talk about, but I can at least tell you about what's there. There are several recipes, but they're much less of a focus in Cosmo than in either 19th-century magazine. Cosmo's food content focuses on "easy" or "convenient" recipes, almost more like "food hacks" for how to use up leftover ingredients, or make otherwise boring meals more interesting. They're clearly not aimed at people who do serious cooking on a regular basis . . . which is fine, because I am absolutely not someone who does serious cooking more than twice a year. Godey's magazine, in addition to three and a half pages of recipes for preserving fruits and veggies and carving various kinds of meat, includes 6 recipes or "receipts" sent in by readers. While these receipts are for much more complicated dishes than the ones in Cosmo, the way they're written is pretty similar : Very few formal measurements or cooking times, a minimum of detailed steps, several short recipes fit into a small amount of page space. The 1897 Harper's Bazaar has fewer recipes, and more randomly spread-out, but there is something extremely relatable about this little article on uncooked deserts for when it's too hot to use the stove or oven.

Something that is noticeably missing from all of the modern magazines, but present in all of the 19th century ones, is literary content. It was common for magazines to publish short stories, poetry, or even serialized chapters of a novel. This is how Jo March in Little Women published her writing. The format became especially popular with Charles Dickens' The Pickwick Papers which were first published in 1836, and even the Sherlock Holmes series was first created for serialized release in The Strand magazine. Serialized publishing was kind of like hedging one's bets for book publishers: If the serialized magazine chapters were unpopular, they hadn't wasted money producing a bound book that wouldn't sell. If it was popular, then they knew they had something that would do well as a full volume too.

But none of this is part of any of the modern magazines. Clearly human beings still read poetry and stories and novels. But, because books are much cheaper and easier to produce and buy, I could see magazine publishers wanting to use that space for something more profitable as demand changed. Maybe that's why there's so much more advertizing . . .

Also, in the 19th century, the internet and television and even radio didn't exist, which really only leaves reading as the available form of leisure media. That's what's around for you to do in your downtime, when a 21st century person would watch a movie or scroll through TikTok. I'm not a media historian, so this is a guess. But it does make a lot of sense to me that people are still going to want something relaxing to do during their free time. I almost feel like reading a short story or poetry is the equivalent of me wanting to watch a Youtube video instead of a whole movie. So there's that same demand, and having short stories and serialized novels in magazines is a way to meet it.

I was a little surprised to see medicine as a topic in three out of four magazines : both 21st century ones, and the 1857 Godey's. That said, the subject matter was verrrrrry different. From what I can tell, Godey's in the 1850s had a reputation for being this very practical, useful resource with lots of everyday information, and the two medical articles are in that vein as well. There's a brief article on caring for one's eyesight, and a longer one detailing how to provide in-home care to someone fighting off an illness. Illness and caring for the sick was a much bigger part of everyday life in the 19th century than today, so the average reader would have plenty of chances to make use of this advice.

As for the 21st century articles . . . given Cosmo's reputation, it will surprise no one that all of its' articles on medicine discuss sexual and reproductive matters in extremely frank terms. But the quality is drastically better and more useful than that reputation led me to expect. Instead of questionable or outright dangerous "relationship" advice, all four articles in the 21st century magazines fall squarely into the category of "things your doctor should tell you about and hasn't". There's a detailed article on medical discrimination and advocacy for LGBTQ+ folks, which, like . . . there shouldn't have to be magazine articles about finding a doctor that won't discriminate against you, but I'm really glad there are. The article in 2021 Harper's Bazaar about core exercises is a bit more trendy and sensationalist, but honestly, I'm just happy to see useful discussion of how to care for the human body. It's not the 19th century anymore, and it's about time we learned to talk about it.

Oddly, what struck me as being the most similar and relatable was all of the news and culture articles. We think of the culture and social attitudes of the 19th century as being totally alien, but despite that . . . I was reading through 19th century Harper's Bazaar and right away, there was an article about the politics of celebrating the 4th of July . . . to go with Cosmo's article about Juneteenth as a holiday. Another talked about the author spending a social season in Paris, reviewing the plays and paintings they'd seen and what celebrities had driven by in their carriages. Another gave commentary on a womens' tennis tournament, and except for the differences in language it read just like modern sports commentary! . . . although admittedly sports commentary is not something I read a great deal of.

I will say this: I am quite pleased to see how much progress has been made on what issues can be talked about in a "womens'" magazine. Not that long ago Cosmo had this reputation for having nothing of substance to say at all, but now it's got political and social commentary that's a lot more useful and realistic than some actual news sites! I can't remember the last time I saw an article about disability justice and representation in a mainstream publication, certainly not one that wasn't inspiration porn. But here is Cosmo with an article calling out ableism directly, by name, in several pieces of popular media. If I started talking about 19th century attitudes about disability I'd basically be dinosaur-screeching all day, so we'll leave off with saying the best of those attitudes was to pretend disability doesn't exist.

All that said, some of these 19th century articles on social issues felt extremely relevant, even a hundred and seventy years later. In Godey's magazine, there's a piece written about fatherhood that admonishes men to stop throwing themselves into their jobs to avoid emotionally engaging with their children. To stop thinking of money as being their only or most important contribution to their family. This is still something we deal with in the 21st century! The world has changed so much in the past twenty years, let alone the past hundred and fifty . . . and yet, here I am reading from a century-plus-old magazine about some celebrity's wedding dress, and how hard it is to get on with a sister-in-law, and what books I should bring on vacation with me.

So herein lies the point— and, let's be honest, the point of most of my deep-dives into history : The past may have been very different, but people were not. We have been acting like, well, human beings for at least as long as magazines have existed. Probably more like millenia. We talk about fashion trends. We talk about what celebrities are up to. We talk about what our fellow human beings are wearing, or eating, their relationships and communities . . . We look for connection. In essence, we are, and always have been fascinated by what our fellow human beings are doing, to the point of inventing magazines just so we could talk about it more.

Which, I, in turn, find fascinating.

If you also enjoy hearing about the realities of the human condition through the lens of fashion history, subscribe, because that's what we do here! Okay, sometimes we also sew pretty dresses, but that totally counts. If you want to fund further fashion history nonsense, you can contribute to the Small Dragon Tea Fund over on Ko-Fi! Don't forget to like this video, and tell me in the comments about the most interesting thing you've read in a fashion magazine. Next time you see me it'll be at CoSy, CosTube's yearly free online convention . . . or, if it's after August 22nd, you can still see me there because all my content will still be up! Until then, keep on learning about the world and the people around you. Bye~

Oh my gosh. Cosmo noticed us costumers. They know.